Can learning aids help public officials deliver work better?

We developed a competency-based, self-assessment learning measurement toolkit to meet the increasing demand for practical tools that enable public officials to upskill on the job.

-

Date

July 2022

-

Areas of expertiseClimate, Energy, and Nature , Governance , Health , Research and Evidence (R&E)

-

CountryIndia

-

KeywordsUrban policy and planning , Climate governance , Adaptive management , Capacity building , Data collection , Diagnostics , Evidence use , Impact evaluation , Policy implementation , Policy options , Research uptake , Technical assistance , Public Sector Governance (PSG) , Public Financial Management (PFM) , Accountability , Fiscal decentralisation , Health service organisation and delivery (HSOD) , Health systems governance (HSG) , India Health Hub , Covid-19 , Primary Health Care , Water sanitation and hygiene (WASH) , Child protection , Monitoring, Evaluation, and Learning (MEL) , Research Management , Qualitative Data Collection , Social Media Listening

-

OfficeOPM India

-

ProjectDesigning a learning tool to assess the competencies of public health managers

|

30-second summary

|

Global development over the last few years has highlighted the need to modernise government systems, approaches and processes. Learning and development within public bureaucracies is no exception. Such an emphasis on guided learning has gained prominence in national policymaking in LMICs such as India, with the government rolling out a National Programme for Civil Services Capacity Building for upskilling of public officials. These initiatives recognise that public officials often lack a conducive environment for on-the-job learning, training ecosystems are often fragmented and poorly equipped, and opportunities are limited to individual innovation and initiative. Facilitated capacity development is then considered a critical means to increase the state’s implementation capacity to deliver on national goals.

Predictably, there is an increasing demand for practical tools, tech-based approaches and job aids that empower public officials to upskill on the job. We recently developed a competency-based, self-assessment learning measurement toolkit for public health officials to critically reflect on their proficiency to undertake their roles. The guided tool helps the officials understand and track the specific knowledge, skills and behaviours expected in their role, to engage with their own strengths and weakness and to recognise areas where they might require further support.

In this blog, we provide some of our key learnings on developing professional development tools that are relevant to evolving bureaucracies.

Simple and easy to use

Bureaucrats in LMICs are typically crunched for time and resources. To ensure that the tool is practical and easy to use, it adopts a ground-up approach that is closely aligned with staff’s de facto responsibilities, rather than relying on borrowed or normative measures of what they should do.

We borrowed administrative parlance that bureaucrats are familiar with and built the initial competency framework through participatory consultations with the role holder, their reporting manager and reportees. A self-assessment route was proposed to ensure that the tool could be used at staff’s convenience with minimal time requirements.

Participatory and transparent

Assessments in bureaucratic settings are usually associated with administrative performance management, often with punitive rather than enabling underpinnings. In the context of LMICs, it is crucial for professional development tools to be developed and used in participatory ways. While learning assessments for public officials can typically be conducted in many ways including tests or on-the-job observations, we propose self-assessment in LMIC contexts till learning approaches gain wider traction and acceptance.

Self-assessments encourage the respondents to critically reflect on their performance and to be more aware of their strengths and weaknesses. Public officials engaging with professional development are also more likely to perceive self-assessment as less threatening than other evaluative methods. Our research showed us that self–assessments are often considered the most feasible method in LMICs as they require minimal administrative overhead, limited budget and time on the part of the government to implement.

Providing full disclosure to users is also critical towards building wider acceptance for learning approaches. We encourage a dialogue with the user, providing clarity about the capacity development objectives of the assessment and transparency about how the information will be used further.

Making it as inclusive as possible

We actively avoid using words like ‘ambitious’ or ‘self-starter’ to keep the language as neutral as possible to avoid adding bias to the tool. This is quite critical as gender-related issues are deeply rooted in many public health systems, and bureaucracies more broadly. The tool intentionally integrates gender-sensitive language, builds an understanding of social and contextual factors in the planning and delivery of services, and advocates for budgeting with gender considerations.

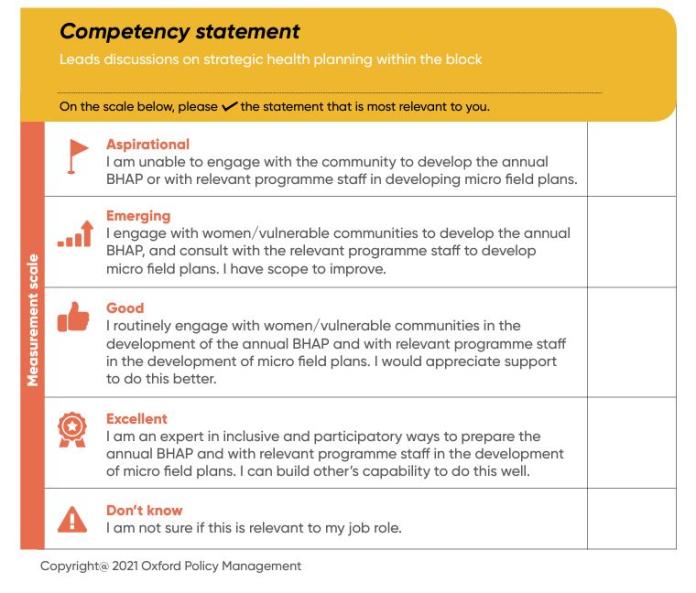

The categories of learning measures have been framed in a positive way to facilitate constructive review rather than corrective. These include: ‘Aspirational’, ‘Emerging’, ‘Good’, and ‘Excellent’. A thumbnail of a related portion from the toolkit is provided below.

Figure 1: Example of how learning tools can be framed positively.

Integrating the tool into professional development assessments

A change management reform of this scale needs significant ownership within public systems. It is imperative that professional development tools are deeply grounded in the realities of the department, administrative level and geography where they are to be implemented so that they are not relegated to another check box exercise. Tool development processes and methods could be replicated across sectors to make them relevant to the wider public system. Ideally, such tools should be refined through learning by doing exercises.