Informed consent is needed in Pakistan’s marriage contracts

Researchers working on our EDI project look at suggested changes.

-

Date

May 2019

-

Areas of expertiseResearch and Evidence (R&E) , Cross-cutting themes

-

CountryPakistan

-

KeywordsGender, equality, and social inclusion , Office of the Chief Economist , Monitoring, Evaluation, and Learning (MEL)

-

ProjectEconomic development and institutions (EDI): cutting-edge research to shape policy reform

Authors: Kate Vyborny, Erica Field, and Hana Zahir

The degree of freedom that women enjoy over key life choices such as whether, when and whom to marry and divorce are intrinsically valuable human rights with potentially important welfare consequences for women and children. Over the last half century, there has been substantial progress in family law, with some estimates suggesting that half of the laws worldwide curtailing women’s legal rights over marriage have been removed. Despite this, women’s rights are still curtailed in many settings, and - perhaps more consequentially - in many contexts, the laws on the books are substantially more progressive than what happens in practice.

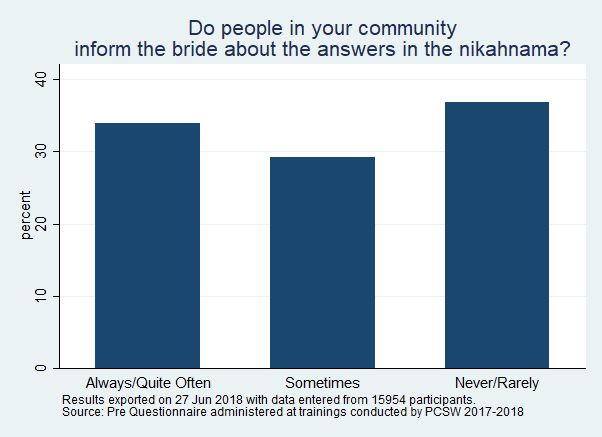

In theory, women’s rights are a crucial part of Pakistan’s marriage laws. This is true in both longstanding legislation and through legal reforms that took place in 2015. Under current laws, forced or underage marriage is illegal, while the marriage contract (also known as Nikah Nama) is a legally binding agreement that specifies issues ranging from divorce rights to financial terms. Consent of both bride and groom is the key requirement. But in practice most brides, as well as their families, don’t understand the content of the contract they are signing. Consent without knowledge isn’t really consent.

The Punjab Commission on the Status of Women (PSCW), a government body in Pakistan, launched an initiative in 2017 specifically designed to address this deficit by training the officials who conduct and register marriages in the region: marriage registrars. Punjab, a province of over 100 million people, has over 40,000 marriage registrars; currently, almost half have received training through this program. In collaboration with the PCSW and the Oxford Policy Management’s Economic Development and Institutions (EDI) project (funded with aid from the UK government) and J-PAL Governance Initiative, we assessed the real progress towards informed consent for marriage, education, regulation and further ramifications.

Regulation and ramification

The position of a registrar is commonly held by an Imam (worship leader of a mosque). There is no formal qualification mandated for this position. In our baseline survey of approximately 20,000 registrars (which PCSW are using in their advocacy), we found that the majority of them offer critical pieces of advice to families — such as whether to grant the bride the right of divorce in the contract — and we found that 90% of registrars had never received any training for this crucial role. They were neither aware of many basic details pertaining to family law, such as the minimum age for marriage or the requirement of informed consent, nor that they could be punished for a violation.

Currently, it is theoretically possible that registrars can be punished for legal violations such as underage marriage or forced marriage, and a 2015 reform increased both registrars’ legal responsibility and potential punishments, but this is seldom enforced in practice.

Impact of training

The PCSW’s project highlighted the importance of educating registrars on family law in such a scenario. The training increased the proportion of registrars who said they will explain details of the marriage contract and also ensure that the bride understands all contract terms before giving her consent.

We analysed 14,000 marriage contracts that were completed before and after the training. We found that the training reduced by more than a third the number of incidents in which registrars illegally crossed out the bride’s option to initiate divorce, rather than asking the bride and groom how they want to complete this section of the contract.

As part of its 100 Day Legislative Reform initiative, the PCSW is using the findings of the training project and the impact evaluation as a baseline and advocating for more gender progressive marriage policy. Some of the PCSW’s proposals include:

- a directive for registrars to counsel both the bride and groom on the meaning and implications of the contract;

- obligatory checks of age documentation; and

- raising the legal minimum age of brides from 16 to 18, i.e. equal age of consent for the bride and groom.

The PCSW believes that such changes would help prevent underage marriages. We observed that in 57% of cases the bride’s ID cards were missing – meaning the registrar did not verify whether they were underage.

In the wake of the PCSW’s initiative, Pakistan’s Council on Islamic Ideology has already announced a review of the marriage contract form. It is considering simplifying the terms and conditions of the contract for brides and grooms, and making it more difficult for marriage registrars to illegally override women’s divorce rights.

The way ahead

In the next steps of the study, we will survey women recently married by newly trained registrars to find out whether interacting with informed registrars resulted in more favourable contract terms for the bride, and also evaluate whether they understand the contract they signed by comparing their survey responses on contract terms to the actual contracts registered on the books. We also plan to test whether the registrars still remember what they learned – to help understand whether and how often follow-up training should be provided.

The better the education and training that registrars receive about the marriage contract, laws and their own responsibilities, the better the guidance they will be able to give to families. This successful legal change could impact the lives of the 50m women of Punjab province, and may be used as a model for legislative changes in the other provinces as well.

In addition to training registrars, the PCSW is currently planning to directly engage with brides, grooms and their families. The commission has already piloted an initiative to inform young women about their rights in the Nikah Nama. In the next stage of the evaluation we plan to study how this interacts with the marriage registrar training.

Changing the law on the books to enhance women’s rights is important – but it is only the first step. To make reforms work in practice, government officials, influential community members and women and families must be aware of the law. The PCSW’s initiative and our study will help to understand how education and awareness campaigns can lead to the fulfilment of women’s rights in practice, not just in theory.

Kate Vyborny is a Postdoctoral Associate in the Department of Economics at Duke University. Her research interests include urban development, particularly the effects of policies on public transportation and land use; and micro evidence on the effectiveness of policies to improve institutional performance with a focus on gender.

Erica Field is a Professor of Economics and Global Health at Duke University specializing in the fields of Development Economics, Health Economics and Economic Demography. Her research interests include the microeconomics of household poverty and health in developing countries, with an emphasis on the study of gender and development.

Hana Zahir is a Project Manager at Centre for Economic Research Pakistan (CERP). She is an alumni of Lahore University of Management Sciences (LUMS) and her research interests include the economics of poverty through a gender lens.

Image credit: PCSW. A version of this article previously appeared at EIU Perspectives.