Accelerating the response to climate change ahead of COP24

Ahead of COP24, Marwah Maqbool Malik from our Climate Change and Disaster Risk team looked at global warming challenges raised in the IPCC report.

-

Date

November 2018

-

Area of expertiseClimate, Energy, and Nature

-

KeywordsClimate policy and finance , Disaster risk , COP

In anticipation of COP24, there was an increasing frenzy of emotion, and expectations (or a lack thereof) from the conference. Climate change experts, activists, environmentalists, and those most vulnerable to climate change eagerly eyed Katowice, with the hope of a renewed, unconditional, irrevocable fervor and commitment to take on the battle for survival. On the other hand, climate deniers – who surprisingly remain (and continue to grow) in large numbers – waited to revel in the conference’s failure to reach any consensus.

The 24th Conference Of Parties (COP) essentially tried to a) take stock of countries’ policies and actions to date, towards fulfilling the Paris Agreement on Climate Change, and b) draft an operational ‘agreement’ that will lay out rules for implementation of the Paris Agreement. As ambitious as both these goals are, they are also increasingly important in the context of the recently revealed IPCC report.

A picture of looming doom

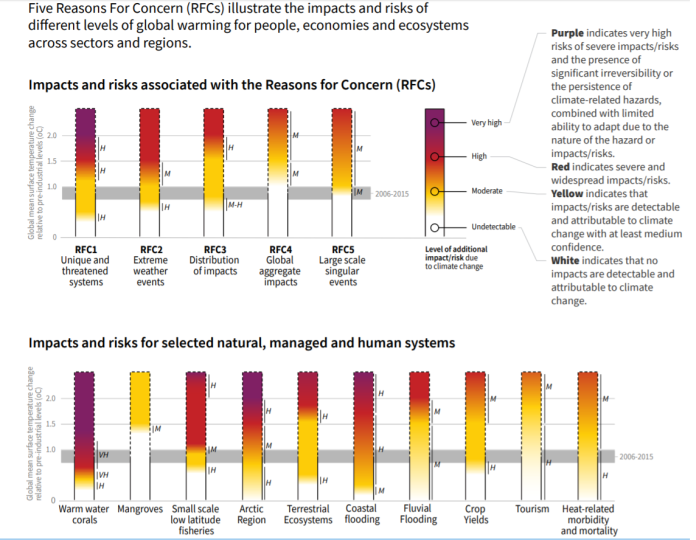

The message of the report is stark: If business-as-usual is practiced across all sectors, we are going to surpass the 1.5°C mark sooner than was predicted earlier – as early as the year 2030 – possibly reaching the 2°C mark which will result in wide ranging impacts to both natural and human systems, with a high probability of irreversible changes taking place around the world. From among the IPCC’s five 'Reasons For Concern' risk classifications, at least four now lie in the medium to high category of impacts at a warming of 1.5°C; the picture at 2°C is bleaker.

Rate and magnitude of global warming aside, the impacts of warming regionally (and more locally) will depend on geographical location (small islands, low-lying coastal areas, and drylands being worst affected), socio-economic status of communities (least-developed countries and indigenous people) and associated vulnerabilities (local communities dependent on agriculture and coastal livelihoods), as well as the choice of mitigation and adaptation approaches opted for. In other words, climate change impacts will hit the poorest and most vulnerable communities (countries) on the planet, the hardest.

So, can COP24 be a gamechanger?

It has the potential to be. Climate change has already taken full force and the task at hand now is that of slowing it down and adapting to its impact. This will require much more than the world has already committed to. There is a need to go beyond verbal commitments and launch into action mode where the overarching goal is to mitigate and adapt in a participatory and socially inclusive manner, aligning these actions with economic, social and sustainable development. Given COP24’s mandate, there is an excellent opportunity for countries to build such a framework and operational plan, which if executed with full force might help the world limit global warming to under 1.5°C.

This begs the question: will such a plan be made, let alone be enforced?

The answer isn’t simple and rests primarily on whose voices will dominate negotiations, what action plans will be agreed upon and how will countries be held to account?

The countries/regions most vulnerable to climate change – such as small island states and most developing countries in Africa and Asia – would need to rally their forces to put forth a stronger voice. On demand should be concerted action on climate change from the world at large, and commitments from the developed world to actively partake in mitigating and adapting while also enabling developing and least developed countries (LDCs) do the same.

Importantly, while a range of adaptation and mitigation actions will be available to countries, given that climatic impacts permeate disproportionately across and within regions, any proposed solutions would need to be entrenched in local contexts. Here again, voice of the most vulnerable regions (communities) must drive the agenda as they can bring to the table, indigenous knowledge and contextualized solutions, especially for adaptation, that can help effectively tackle climatic impacts.

Relatedly, important enablers for any action plan to take place would include sufficient institutional capacity, strong governance, and political will at local, national and international levels. These tie in with a multi-level climate governance framework where policy, planning and action on climate change happens at all level of governance, including the lowest tier i.e. neighbourhood for example; such a framework gives birth to innovative solutions to battle climate change and ensures ownership of actions, even at micro-level. Our Action on Climate Today (ACT) programme that has been working with policymakers and other stakeholders across South Asia has been able to effectively build institutional capacities at the lowest tier of governments; the experience of mainstreaming climate change in local government planning in India provides useful insights which policy makers in developing countries and LDCs could benefit from as they prepare for COP24.

The gigantic battle against climate change naturally comes with a huge price tag, most of which the most vulnerable regions are unable to pay for. Since these financing needs cannot be met merely with public funds, there is a need to mobilise international and local finance from private investors, asset managers, international development agencies and banks, and multi-lateral institutions. Strong voices at COP24 must demand that developed countries be held responsible for delivering on their financial commitments as this finance will be key to ensuring human ‘corrective’ action is able to limit global warming and its oncoming impacts.

Climate change is happening now and while there is hope that we can still salvage our planet from irreversible destruction, the onus of action lies on all of us – more so on the developed countries who have the means to be actors, as well as enablers for other countries. A faltering commitment from the developed world and/or the inability of the most affected to come forward loud and clear, could very well derail any positive outcome from COP24. But more disturbingly, it would destroy, perhaps our only chance, to save life on this planet as we know it.