Practitioner Insights: capacity development for better results

People often talk about 'capacity development', but what does it mean in practice?

-

Date

January 2018

-

Area of expertiseGovernance

-

KeywordPublic Sector Governance (PSG)

-

OfficeOPM United Kingdom

‘Capacity development’ might well be the idiom most dear to development practitioners, on a par with ‘political economy’. So widespread its use and so broad the consensus around how ‘essential’ it is to any development project that the boundaries of its definition have become blurry. For many practitioners, capacity development refers to training local counterparts on some of the critical components of their programme. Often the choice of training content is arbitrary, consultants cherry -picking some of the elements that feel important to them, for whatever reason. Even worse, I have seen teams assuming that the mere presence of international experts working next to local government counterparts will lead to capacity development.

[button-link text="Explore the rest of our Practitioner Insights series" link="https://www.opml.co.uk/search?campaign_tags%5B%5D=practitioner-insights&contenttypes%5B%5D=blog"]

There has to be a better way to do capacity development. Some argue that only eight of the countries traditionally known as ‘developing’ have built strong state capability in the past 50 years, while almost half of the developing countries currently have a weak or very weak state capability. If this is correct, then international development practitioners need to take a step back and question the way we have all been doing capacity development to date.

Context analysis

In Oxford Policy Management (OPM), I lead the Policy Execution Hub. Our main endeavour is to analyse the points of failure when executing government policies (especially those that seem perfectly designed) and provide support to the sectoral teams on tools, mechanisms, and structures that help in addressing those challenges.

For us, the starting point of capacity development activities is a mapping of functions that government officials need to get the job done successfully, and the competencies required to do this. Once identified we look at the organisational setup to identify resources, processes, and procedures that may support or impede the capacity development we are planning. An additional institutional review will map both formal and informal rules of practice and behaviour, starting from the laws and regulations to the social norms and culture dominant in the respective public administrations.

Individual competencies

One of the most common failures in policy execution is that experts focus exclusively on technical competencies; that is, the specialist knowledge, skills, and practices. In most cases, competencies required to perform a specific function in the public sector are not exclusively technical. Individual performance also relies on professional skills, behaviours, and attitudes. For example, business development experts I have worked with in the past were primarily interested in building capacity for the government officials to review the economic viability of project proposals for local development. For them, organising a few training sessions and providing on-the-job support was the most comfortable task.

It was more challenging though to support the development of their professional competencies and promoting enabling behaviours aligned to the functions they were expected to perform. Professional competencies were even more critical than usual in this case as the experts were part of a newly established department and most of them only recently graduated. Moreover, whilst many were aware of the most relevant theories, many did not know how to facilitate meetings within the organisation, organise consultations with the business community, or undertake negotiations with investors, and so forth. The lack of professional competence undermined the functioning of the department far more than the lack of technical skills.

Function-centred competencies framework

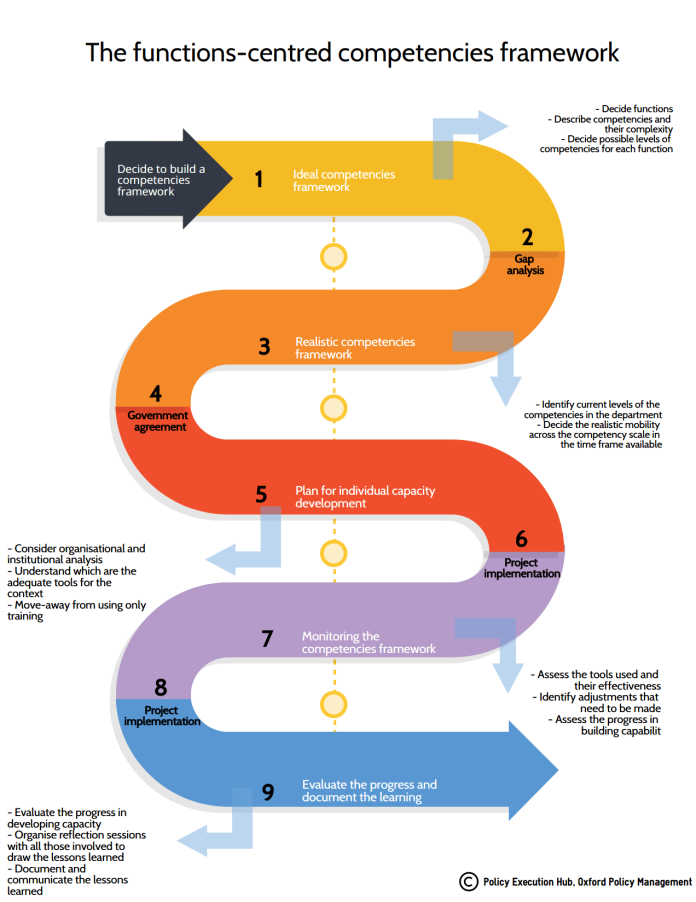

A systematic approach is essential when trying to frame the actions needed for building capacity. One solution that we’ve started testing is a project-specific function-centred competencies frameworks.

Once we’ve agreed on the functions to be performed by employees and the corresponding competencies required to perform those functions, we undertake a gap analysis to decide the current levels of competencies in relation with the ideal levels. Based on this, the project team can plan the desired (realistic) progress on the competencies scale and have a tool to monitor progress, and evaluate the effectiveness of the intervention.

The competencies framework can push sectoral experts beyond their comfort zone where opportunistic training with an international expert and study visits take centre stage. It encourages health, education, or environmental experts to work more closely with governance experts to approach and consider problems more confined to the context, not just to their respective subject matter.

We have applied this logic to some OPM-led programmes. Our team has been working closely with climate change, business development, social assistance, and education specialists. For instance, the most significant application of this approach was on a regional climate change programme that aimed to provide programmatic capacity development for mainstreaming climate change in decision making and public policy. This framework allows for systematic analysis of the competency gaps, realistic planning of what is potentially possible to achieve within the duration of the programme, and provides a framework for programmatic investment in prioritised areas.

Key takeaways:

- Effective capacity development needs to be systematic and to start with the functions we want to support building in the departments, organisations, or governments. It doesn’t start with the skills we want to build in individuals.

- Individual capacity development needs to complement technical competencies with strengthened professional competences and promotion of the behaviours and attitudes needed for the job.

- The analysis of the organisational setup and institutional environment will help develop a realistic function-based competencies framework.

Alexandra Nastase is a senior public sector governance specialist with OPM and she is leading the Policy Execution Hub. In the past eight years, she has been working with and for governments in Europe, west Africa and south Asia, by providing governance advice on how to drive government performance, reduce corruption, and improve administrative capacity at individual, organisational, and institutional level.

[button-link text="Explore the rest of our Practitioner Insights series" link="https://www.opml.co.uk/search?campaign_tags%5B%5D=practitioner-insights&contenttypes%5B%5D=blog"]