Protecting social sector financing post covid-19 in the Middle East and North Africa

Governments are facing tough choices on how to finance the social sectors post covid-19. We set out recommendations for revenue raising and reprioritising spending.

-

Date

July 2020

-

Area of expertiseGovernance

-

FeedWEF

-

KeywordPublic Financial Management (PFM)

The economic impact of the covid-19 pandemic will be felt for many years. Yet the way the shock impacts both the demand for public services and the public finances available to supply them, varies significantly across the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) countries. However, one of the universal and immediate consequences of covid-19 is a drop in government revenues, just as a fast response is needed to support the health sector and maintain people’s livelihoods.

All MENA governments are facing tough choices on how to maximise their limited fiscal space - budgetary room - in terms of revenue raising, borrowing, aid, and how to prioritise and cut expenditure.

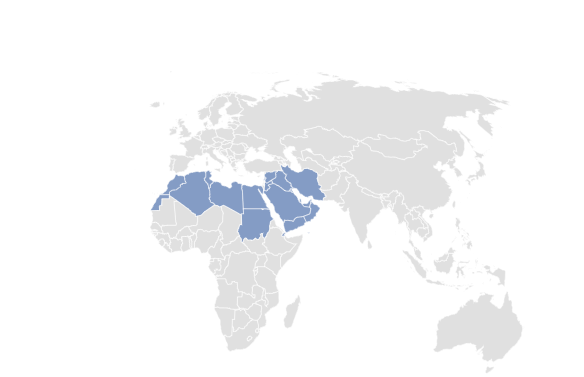

Map showing the countries in the MENA region

Spending in the social sectors such as health, education, nutrition, water sanitation and hygiene, child protection, and social protection, is critical for future growth; by supporting human capital development, and for the realisation of fundamental human rights and freedoms, as encapsulated by the Sustainable Development Goals. Governments need to consider the consequences of the shock on public finances and how their response could affect social outcomes, as there is no one-size-fits-all solution.

The fiscal shock – and possible solutions – will vary across MENA countries

The MENA region has broadly suffered from low growth over the last decade, as well as volatile oil prices, high public debt and conflict. Despite being grouped together geographically, the MENA countries public finance structures vary, and so the impact of the shock and needed response, will also vary substantially.

- The oil exporters will be hit hard by the collapse in oil prices. Oil makes up over 90% of exports from Kuwait, Iraq and Algeria; with Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Oman and Iran not far behind. These countries have large financial buffers, but are less diversified and will not be able to react quickly. Commitments such as high public sector wages and pensions and debt interest payments, mean even more pressure to cut other areas of spending.

- But the oil importers will be impacted too. Countries like Morocco and Tunisia will enjoy lower energy prices, but they tend to export labour to the oil economies, so will be facing reduced revenue from exports and remittances.

- Countries with already unsustainable debt level will have limited scope to borrow more. Bahrain, Lebanon, Jordan, Egypt and Sudan all have debt levels greater than 90% of their GDP.

- Countries facing fragility and conflict will need international support. These countries – Syria, Iraq, Libya and Yemen – will find it difficult to increase revenue or debt, or to implement a unified national response. Any budget reallocations are from a low base and will lead to shortages in other sectors.

What options do governments have to protect the social sectors?

Official development assistance and concessionary loans

As government revenues fall, the remaining options to recover fiscal space for the social sectors will vary by country. Taking on debt to fund immediate needs in health and social protection might allow governments to reprioritise their domestic revenue to other social sectors.

Timing is critical for the effective use of resources as some options, such as targeted grants as part of official development assistance (ODA), are better suited to the immediate response; whilst reforms aiming to improve the efficiency of spending and service delivery, will act in the medium term. Whichever options are feasible for a country (ODA, debt, budget reallocations), they need to be implemented with a focus on efficiency to maximise the value of public spending, and equity to target spending to the poor and disadvantaged.

Most MENA countries are high-or middle-income and so less likely to receive significant ODA from multilateral organisations. ODA will therefore be most relevant to the lower income countries (such as Yemen, Syria, Sudan and Djibouti) that are already eligible for International Development Association support ;Yemen has already received a $27million IDA grant. ODA to these countries might also come in the form of debt relief, such as the International Monetary Fund’s scheme for debt relief in response to covid-19, which Djibouti and Yemen have already benefited from.

Concessional loans for the covid-19 response can be accessed from the World Bank, IMF and Islamic Development Bank. This is appealing in the short term and many countries have taken advantage of new debt or loan restructuring programmes from the World Bank and the IMF. As with any debt, it must be sustainable to manage, and while long term interest rates are expected to remain low, this is still a particular challenge for countries already highly indebted. Governments should also consider the medium term impacts of the conditions that come with debts, such as limiting the public sector bill and what this will mean for service delivery in the future.

Re-prioritisation of spending

Re-prioritisation of spending will be necessary across all countries in the immediate response, medium term reform, or both, and the following factors should be kept in mind:

-

Avoid blanket cuts across all ministries and programmes – shaving a portion from every budget is not effective or efficient as it ignores the structure of spending in different sectors. Where ministries are tasked with finding budget cuts, they should prioritise households’ access to services, especially the most disadvantaged households, as well as the long run prospects for recovery.

It is difficult to cut the wage bill, particularly in the social sectors, where it makes up a large part of the inputs to service delivery. Public sector employees often make up a large portion of employment and cuts could also lead to social unrest. Capital projects will need to be paused as a priority. - Don’t overlook the cross-cutting sectors which play a preventative role in avoiding negative and costly future outcomes. Nutrition and child protection are often less visible sectors, but they have long term implications for human development and economic growth.

- Service delivery which is funded at decentralised levels should not be forgotten. Making cuts to local governments will have a direct impact on services such as water, sanitation, and often health and education too.

- Efficiency savings can be found in the medium term by reforming systems and better targeting resources. Focusing on providing universal access to good quality basic services will improve the allocative efficiency of spending – the best mix of inputs to meet social outcomes. Investments in social registries and cash transfer programmes will better protect workers in the large informal sectors, who miss out on contributory benefits. Refocusing efforts to provide Universal Health Care through a basic package of care will improve both the efficiency and equity of spending in the health sector.

Reform in social sector financing and service delivery was necessary in many MENA countries even before covid-19. The pandemic has highlighted the need for changes, but these need to be permanent reforms and not temporary measures. Now is a unique moment for the MENA governments to look at their spending and refocus on those most in need.

This blog was written by Caitlin Williams and Nicola Ruddle, from OPM’s Education Financing team. It draws on a report by OPM’s Social Policy Programme and Genesis Analytics to inform and support the UNICEF MENA Regional Office in their response to the covid-19 crisis.