Shock-Responsive Social Protection: findings from our global study

How and when can social protection systems better respond to shocks?

-

Date

January 2018

-

Area of expertisePoverty and social protection (PSP)

-

KeywordsSocial protection , Shock Responsive Social Protection

How and when can non-contributory social protection systems better respond to shocks in low-income countries and fragile and conflict-affected states? ‘Shock-responsive social protection’ could minimise negative shock impacts and reduce the need for separate Disaster Risk Management (DRM) and humanitarian responses — using ‘existing resources and capabilities better to shrink humanitarian needs over the long term’, as recently called for by the Grand Bargain at the World Humanitarian Summit. OPM led a study to strengthen the evidence base around this question, funded by UK aid from the UK Government, through DFID’s Humanitarian Innovations and Evidence Programme.

Our team, which we led in partnership with the Overseas Development Institute (ODI), the Cash Learning Partnership (CaLP), and INASP, have now completed case studies in Pakistan, Philippines, Mozambique, Lesotho, Mali, and the Sahel, as well as a global review of literature on the topic. What have we found? The full Synthesis Report is available to read; below are some of the highlights.

1. How to assess what counts as better?

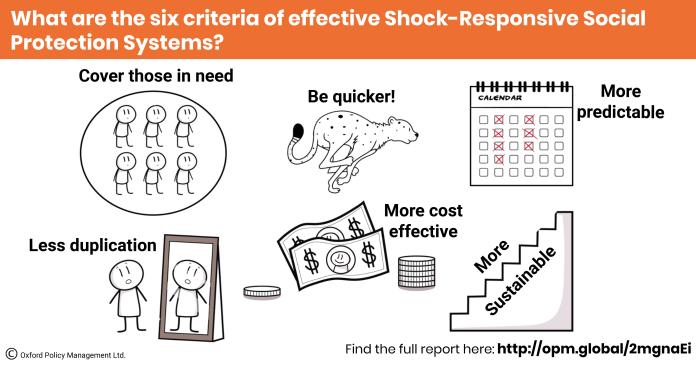

Shock-responsive social protection may not always be the best course to take. So how do we decide between using and adapting existing social protection systems versus other approaches? Our research identified key criteria that could be used:

- Meeting needs: the intervention delivers an equal or greater impact than its alternatives through a response that is better targeted, provides a more adequate level of support, or provides support of a more appropriate nature.

- Coverage of population: increasing the absolute number of people reached, or the relative share of those in need of assistance.

- Timeliness: guaranteeing a timely response to crises to avoid interventions being delivered too late to be of use for the shock they were intended to address.

- Predictability: the predictability of funding for implementing agencies and predictability of assistance for households.

- Elimination of duplicated delivery systems and processes with implications for cost-effectiveness): such as multiple agencies conducting similar targeting exercises in the same communities.

- Sustainability: it leads to strengthened organisational capacity, such as being embedded in government-led systems.

2. What options are there for shock-responsive social protection?

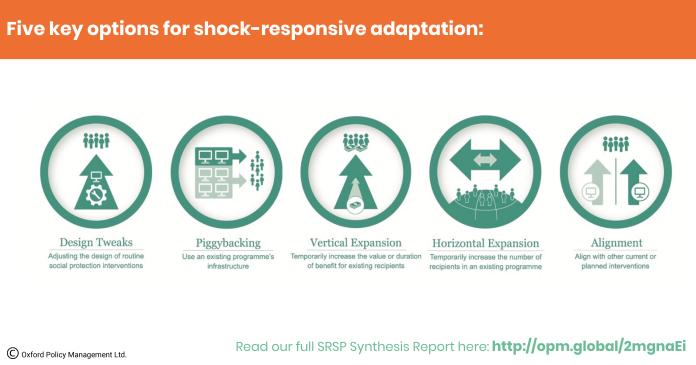

Building on our original conceptual framework developed at the start of the study, we have identified five key options for shock-responsive adaptation that countries may adopt as standalone solutions or in combination (including across several social protection programmes):

Extensive details on these — including full definitions, contextual prerequisites, opportunities, challenges, and risks — may be found in Sections 4–11 of our Synthesis Report, including a useful summary table.

3. And what are the operational and contextual factors we should be keeping in mind?

Effective shock-response through social protection programmes strongly depends on how underlying delivery systems work. Practical factors that should be carefully assessed include the following (discussed in depth in Section 14):

- procedures for needs assessments, data management, and targeting (defining who to support — see also our policy brief on this)

- setting how much support to give (value)

- resilience of payment mechanisms and infrastructure

- communication to beneficiaries and non-beneficiaries.

The design of shock-responsive programmes will also be affected by the overall context for policy-making. We identify five main attributes, extensively discussed in Section 13 of the report: political will, the regulatory environment, organisational capacity and mandates, financing, and conflict.

4. How can humanitarian, disaster risk management, and social protection systems best work together for effective responses to shocks?

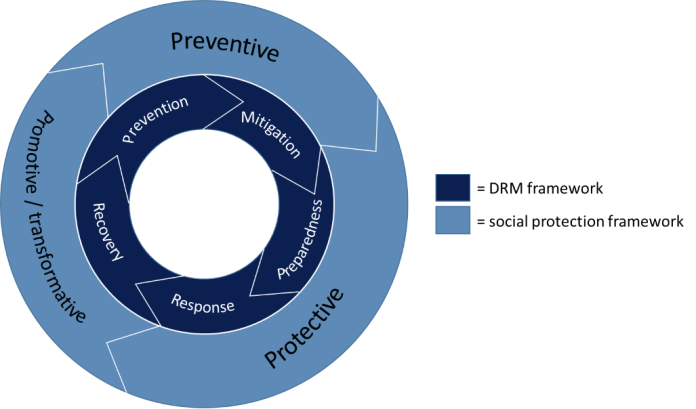

In many countries, collaboration between the social protection, disaster risk management (DRM), and humanitarian sectors is limited. Better coordination is valuable not only between sectors nationally, but also among their representatives at different levels of public authority — regional, national, subnational, and community. Social protection initiatives can contribute at multiple stages of the DRM cycle, offering much more than material support for disaster response, as the figure below shows.

One of the main opportunities for coordination that is often underexplored among social protection actors is the link to existing tools and approaches used by the DRM sector, ranging from contingency plans and early warning systems to post-disaster needs assessments, DRM committees, and laws. See our summary table or full section for details!

5. To conclude, what are the principles for preparing for an effective response to shocks?

The global study identified six principles that should be kept in mind by any actor engaging with the idea of developing shock-responsive social protection systems in their country:

- Strengthening routine social protection is worthwhile in its own rightfor building resilience, while simple ‘design tweaks’ can be implemented to further adapt existing programmes to potential shocks.

- Vulnerability and needs assessments are an essential component of decision making about whether or not social protection is a suitable vehicle for addressing a shock.

- Interventions are likely to work more smoothly if they are planned in advance, through early decision making, active planning, and (where appropriate) early delivery of support.

- Mature social protection contexts have more options in a crisis. Tiny, fragmented, and under-funded/capacitated programmes are unlikely to replicate the kind of response possible in effective mature systems with broad coverage.

- No shock-responsive social protection can meet the needs of all households who need assistance, so coordination with other interventions is essential.

Measuring success in ‘shock-responsive’ interventions is contingent on the identification of appropriate indicators that can be compared across humanitarian and social protection responses, and that cover outcomes and impacts, not just inputs and outputs.

Our report further highlights opportunities for shifts in policies and practice among social protection, humanitarian and DRM actors, read our ‘recommendations’ section for details.