When and how to use digital tech to improve public service delivery

The second of our two-part series on digitising public service delivery

-

Date

December 2018

-

Areas of expertiseClimate, Energy, and Nature , Governance

-

KeywordsEnergy, resources and growth , Public Sector Governance (PSG)

-

OfficeOPM United States

Digital technologies can help governments improve public service delivery. My previous blog post explained this potential and it flagged limitations and risks. Two key lessons emerged. First of all, a range of contextual factors determine whether digital technologies are likely to improve public service delivery. We therefore have to consider carefully whether and when digitisation is an appropriate solution to a service delivery problem. Second, digitisation projects often fail. This means that we have to be much smarter about how we actually implement such projects.

[button-link text="Read the first part of this blog series" link="https://www.opml.co.uk/blog/digitising-public-service-delivery-opportunities-and-limitations"]

How do we decide whether digitisation is the right solution?

Digital technologies present potential solutions to service delivery problems. Problems could include high costs, low-quality or patchy coverage of existing service delivery models, or a lack of information from beneficiaries about the quality and desirability of a service.

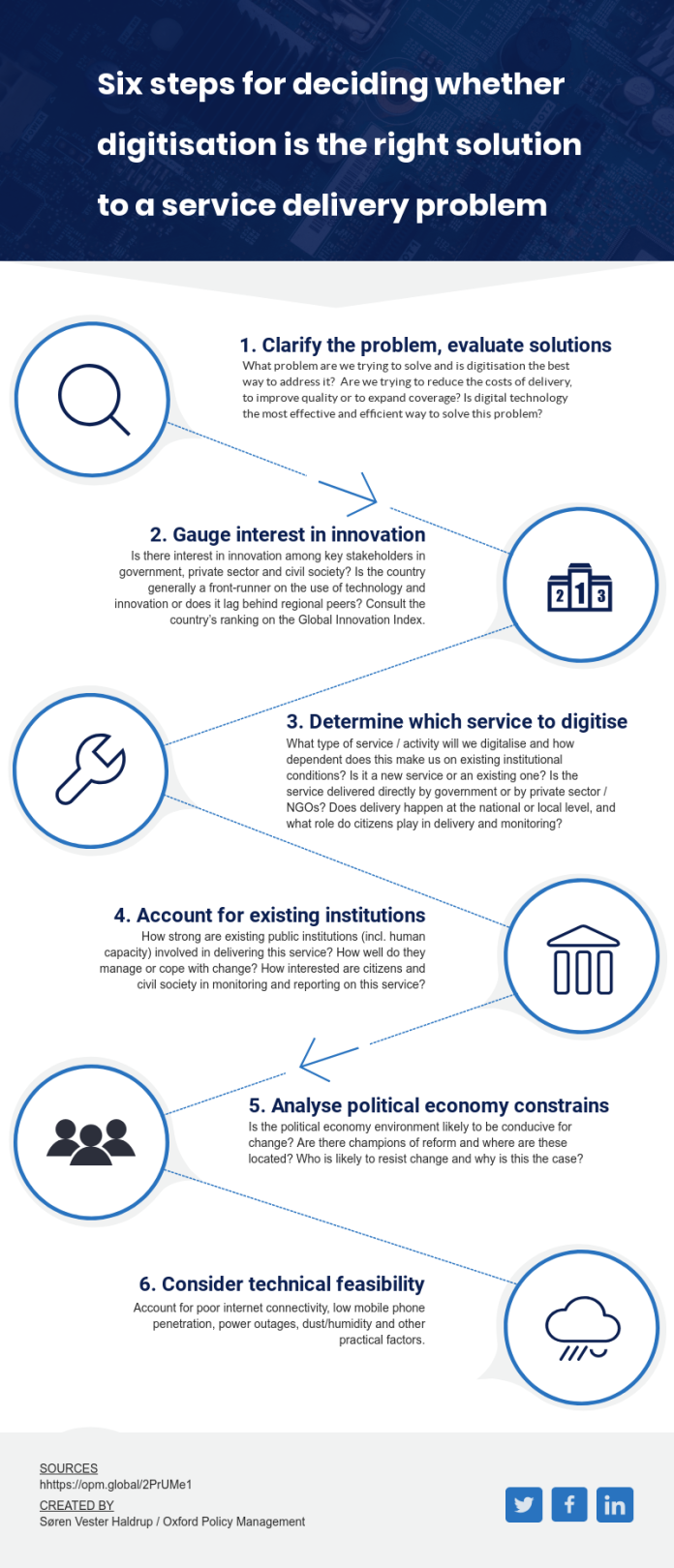

However, digitisation might not always be the best way to solve these problems. In order to decide on whether or not to ‘go digital’, I propose a six-step decision-making process. The visual below explains this process. This approach provides a basis for reflection and preliminary decision making, and I recommend that it is supplemented with more elaborate methodologies for evaluating policy options (read more about such methodologies in this manual for multi-criteria analysis or in Eugene Bardach’s A Practical Guide for Policy Analysis).

These six steps can help us get a sense of whether digitisation is the right solution to a service delivery problem. However, even if we deem digitisation the right approach, it can be immensely challenging for governments and development partners to actually implement the project. The next section provides a series of recommendations on how to deal with this problem.

How to implement a digitisation initiative

Following the process above, we may in some cases conclude that digital technology is the best solution to a service delivery problem. If this is the case, we are then confronted by the problem of how to actually implement the digitisation project.

Implementation is difficult. A simple mathematical example from my favourite book on implementation provides a powerful example. Let’s imagine an implementation process with five decision points (points at which one or several actors have to agree to or actively do something for implementation to proceed). If we assume an 80% probability that implementation will proceed undistorted and without delay at each of these points, then there is only a 50% probability that implementation will happen on time and without modifications. With 70 decision points – not unlikely for a digitisation project – the probability drops to one in a million!

Implementation is not a one-off activity, but a complex, often non-linear, process that involves a series of steps and actions. Various stakeholders act and interact at each stage (or decision point) of the process – some at the political level and some at the technical. The outcomes at these decision points stalls, distorts, or pushes the implementation process ahead. The end result of the process – the actions of front line service delivery providers – is difficult to predict and may often vary considerably from what was envisioned at the beginning. This applies in particular to projects in uncertain and rapidly changing environments such as those in low-income countries – especially when the projects involve digital technologies that are new and untested.

Though this sounds discouraging, there are things we can do to help make sure that implementation succeeds under these difficult circumstances. Below I provide five recommendations:

Recommendation 1: Do a thorough context analysis

It is crucial that a digitisation project is anchored in the local context. To ensure this, it is necessary to first undertake a thorough analysis of the institutional and political context that the initiative is implemented in. For instance, existing legal and policy frameworks, privacy standards and data structures all affect what can and cannot be done. This USAID publication discusses this in relation to digital IDs with a distinction between instrumental and infrastructural approaches. There are various methodologies for doing this type of analysis. The key is to not only take account of government staff capacity and formal organisational systems, policies, and laws, but to also consider how behavioural biases, informal institutions (such as social norms), politics, and patronage shape current behaviours and enable/limit behavioural changes necessary for implementation to succeed. This analysis should shape the focus, scope, and design of the digitisation initiative. For long projects, the analysis should be updated and used to continuously adjust project implementation.

Recommendation 2: Secure support of key actors and build broad coalitions to unlock change

Winning broad support for the digitisation initiative is key, so we should use the context analysis above to identify champions and spoilers, and, together with counterparts, build coalitions for change. Coalitions can extend horizontally and vertically across government, and span the public, private, and civil society spheres. The important thing is that they help unlock change at critical points in the process. The preferences of stakeholders may change over time and their influence can vary according to where we are in the implementation process. Some stakeholders, for instance, hold great sway over procurement decisions, while others influence the behaviours of district-level service providers. As a result, we may have to adapt our stakeholder engagement efforts and the composition of coalitions as implementation progresses.

Recommendation 3: Address the analogue as well as the techy components of digitisation

Effective adoption of technology in an organisation requires significant investments in skills and changes in working arrangements. A digitisation project is therefore about much more than developing the technological fix. For example, IT investments by police departments in the US have been shown to only be linked to improved productivity when they are complemented with organisational changes and adjustments in management practices. For a digitisation initiative to succeed, it will therefore need to take account of and, when needed, address a range of ‘analogue’ things that distort, obstruct, delay, or facilitate implementation. The context analysis will give us an idea of what these things are, and it will provide us with a baseline for measuring progress as we begin implementation.

These analogue prerequisites depend on the context, but usually include the development of existing and new skills and knowledge (including non-technical competencies such as project management and leadership skills); changes to systems and procedures (such as performance management, recruitment, and reward arrangements in a ministry), as well as new policies and laws (such as those related to data privacy, recruitment or procurement). Social norms and various cognitive biases also affect the implementation of a digitisation initiative, so it is necessary to include approaches that address these. To this end, the Behavioural Insights Team has provided a useful overview of the common biases that affect project delivery and organisational decision making in the public sector.

Recommendation 4: Ensure balanced mix of skills in the project team

The teams that implement public digitisation projects vary in terms of their location, membership, and expertise. A team may be ad hoc or full-time, and it may sit within a particular ministry or span several government departments. Non-government staff such as technical experts, civil society actors, or international development advisors, may lead or support the project either as permanent or ad hoc members. Furthermore, development partners may at times have an active or advisory role in the project – especially if they are funding it.

The right team structure will depend on the context. However, in all circumstances we need a broad set of skills and experience. Expertise relating to the required digital technology is of course important, but it is equally important to have access to people with expertise in the variety of analogue components of digitisation. In cases where we require expertise from an external digital technology supplier, we should to the extent possible collaborate with one that understands the local political, institutional, and technical operating context. The leadership of the project team will be crucial as it’ll have to mediate and build trust and understanding between people with very different perspectives and professional backgrounds. This mediation will happen within the project team, as well as more widely between different parts of government and possibly with civil society actors, private sector companies, and development partners.

Recommendation 5: Adopt an iterative and experimental approach to implementation

The implementation of digitisation initiatives in low-income countries is confronted with a double uncertainty whammy. Any initiative working to improve public service delivery in low-income countries (especially one that involves external actors such as development partners) faces complexity and uncertainty due to things such as lack of contextual information, data gaps, a variety of stakeholder groups, and complex political economy dynamics. However, digitisation initiatives have an added layer of complexity, as they entail the development, testing, and scaling of technologies that are emerging and probably have not before been used in the given setting.

If we want to implement successful digitisation projects in these types of environments, then we need an adaptive implementation approach. This applies both to the project as a whole and to the technology development component in particular. The digitisation project as a whole should be designed on adaptive programming principles (for details see here, here, and here) and this requires strong monitoring and learning systems. This type of approach will allow us to design a digitisation initiative that is firmly rooted in local contextual realities. It will also give us the flexibility to adjust our approach based on learning and to tailor interventions to each stage of the implementation process. This approach will also enable us to better identify and manage risks on a continuous basis throughout implementation.

Testing and iteration is also crucial for the techy component of our digitisation initiative. Design thinking is helpful and already an established approach in the world of tech. The users of the digital technology – such as front line service delivery providers and citizens – should be at the centre of this process (read more about user centric design) so co-creation and extensive consultation are key. In this connection, we must also consider risks associated with data privacy and potential bias (watch this video for an extensive account of bias and exclusion risks in tech). In order to save time and money it is useful to develop digital solutions based on the principle of the minimum viable product (MVP). In an MVP approach, the new digital solution is developed with just enough features to satisfy early users, while the final, complete set of features is only designed and developed after considering feedback from the product's initial users.

Following these recommendations will increase the likelihood that a digitisation initiative will succeed, if they are applied to a case where digital technology is indeed a sensible solution to a service delivery problem. However, given the relative novelty of this field, there is still a lot that we don’t know about when digital solutions can help improve service delivery in low-income countries, and how to best implement these types of projects. At OPM, we continue to test and learn from our current initiatives in this space (including this, this, this, and this). We will share what we learn as we go along, and we invite others to join the conversation.

Get in touch with Søren Vester Haldrup and OPM’s Public Sector Governance team. Søren is based in our New York office where he works on public sector reform, political analysis, and technology and innovation for governance.