Why illness needn’t mean bankruptcy: lessons from piloting social health insurance in Bangladesh

Severe illness can bankrupt poor families in Bangladesh, where nearly a third of people live below the poverty line.

-

Date

June 2018

-

Area of expertiseHealth

-

CountryBangladesh

-

KeywordHealth service organisation and delivery (HSOD)

-

OfficeOPM Bangladesh

-

ProjectSupporting the piloting of social health protection in Bangladesh

Many households are only one misfortune away from having to face a choice between catastrophic health expenditure and neglecting their wellbeing.

In order to combat this, the Government of Bangladesh is piloting a social health protection scheme known locally as Shastho Surokhsma Karmasuchi (SSK), supported by the German Government and financed through KfW Development Bank. SSK offers free insurance for inpatient health care to nearly 90 thousand people living below the poverty line in Kalihati — a subdistrict in Tangail district of Bangladesh. If successful, the intention is for the scheme to be extended across the country, which will constitute a major step towards achieving universal health coverage in Bangladesh.

Over its first year, the pilot has provided free inpatient care to more than 400 people. Applicable households were identified through a census and given a card which includes the biometric information for all members of the household.

Early users of the scheme include Mr Abu Hanif and Mrs Hanufa, pictured with their card, above. Both have long-term illnesses — Mr Hanif has a chronic respiratory disease and Mrs Hanufa is partially paralysed after suffering multiple strokes — but they had been unable to afford health care when their symptoms worsened. Since the SSK piloting started in their area, they were admitted at the Kalihati hospital where they received free treatment. After being discharged, they were given two weeks of medication. Currently, however, SSK currently only covers inpatient care: Mr Hanif and Mrs Hanufa can’t afford to continue with their required medications. Recognising this broader issue, the scheme is now working to include free outpatient care from late 2017.

Without a functioning social protection programme, patients had often previously resorted to negative coping strategies, or turned to traditional healers rather than qualified medical professionals. Mrs Nurjahan Begun, pictured above with her husband and son, had obstructive labour during the birth of her first son, requiring an emergency caesarean section. This was done at a costly private clinic, meaning that she and her husband had to sell property and borrow money. For the birth of their second child, at Kahihati hospital, Mrs Begum was able to have a caesarean section without any cost, with the insurance coverage from SSK.

Her husband, Mr Chan Mohammad, was delighted not just about the birth of his child — but also about avoiding impoverishing costs: “This time, I will have some money to buy some toys for my son”, he said.

When Mr Anisur Rahman fractured his leg in a road traffic accident, he opted for non-surgical treatment, because he couldn’t afford the recommended surgery. Mr Rahman’s treatment turned out to be lengthy and expensive itself, though, and he had to borrow money at a high interest rate — but his leg was left disabled. Since Mr Rahman was a rickshaw-van driver, this has severely affected his household’s income. He and his wife are now included in the SSK scheme, but it may be too late for them to benefit from free treatment, at least as far as this injury is concerned. They show how vital SSK will be for other households, and what a difference it could make.

More than just access is needed, though. The facilities being opened up need to be in good working condition, fully equipped and properly staffed; the Kalihati was fully renovated as part of the scheme.

One of the major challenges facing SSK is the community’s lack of trust in public health care facilities. Dr Syed Ibne Sayeed, Civil Surgeon of Tangail district, is keen to overcome this. “My hometown is within the piloting area, and I’ve seen people’s vulnerability to catastrophic health expenses first-hand,” said Dr Sayeed. “People do not have high levels of health awareness and they don’t know about their rights. To tell you very frankly, there was a time when we were not so keen to let people to be completely aware of their health rights — knowing that it would create pressure on us to meet their demand, which we were unable to do with our limited resources. The time has changed. We are now proactively informing them about their rights, we are telling the people that you have the right to seek and receive quality health care”.

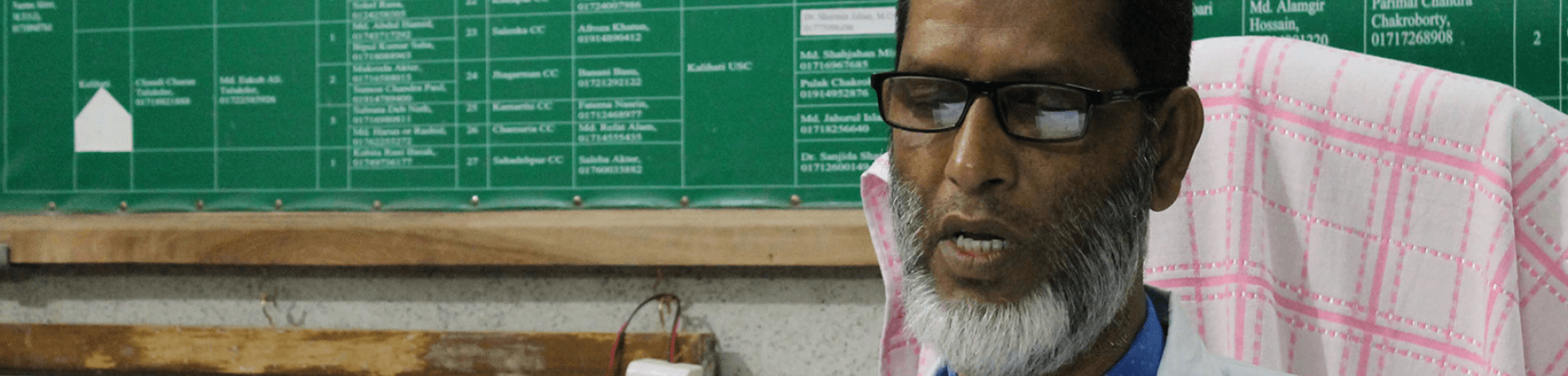

Another challenge, as noted by Dr Belayet Hossain (shown above) who heads the health facility in Kalihati subdistrict, is maintaining staff morale. While health workers appreciate the better accommodation, training opportunities and management, SSK has turned his under-utilised, low-profile health facility into a fully-functioning facility with high patient load and this, in turn, means a higher workload for the health workers without any additional financial incentive.

The next steps of the pilot will look to address this and various other limiting factors. The scheme currently covers 50 diseases and respective inpatient services at public sector health facilities. Cases which fall outside this remit — if surgery needs to take place at a tertiary hospital, if outpatient care is required or if the disease isn’t one of the fifty included — aren’t yet covered. Another open question is how best to include the private sector in service delivery. In the coming years, therefore, there are plans to include outpatient care, two more subdistricts and private sector facilities — but SSK is already an important step towards achieving universal health coverage in Bangladesh, and ensuring that illness needn’t mean financial crisis.

Dr Rashid Zaman is a public health expert and a Senior Consultant of Health Portfolio at Oxford Policy Management (OPM).

Acknowledgements: The author is grateful to the respondents and to Azmal Kabir and Mohammad Asaduzzaman from the technical assistance (TA) team for participating in the field visits. He is also thankful for ideas and insights from colleagues from the implementing agency, the Health Economics Unit of Ministry of Health and Family Welfare of Government of Bangladesh, the funder KFW, and the consortium members of the TA team (Oxford Policy Management, Management for Health and Institute of Health Economics of the University of Dhaka).