After the Pandemic: a global UK?

Low-income countries in Africa face a long hard road to recovery. The UK could catalyse and lead global support and change the future for developing countries.

-

Date

June 2020

-

Areas of expertiseResearch and Evidence (R&E) , Cross-cutting themes

-

FeedWEF

-

KeywordsOffice of the Chief Economist , Evidence use , Research uptake , Research Management

Written by Mark Henstridge, Stevan Lee, and Christopher Adam (Professor of Development Economics at Oxford University).

After the pandemic low-income countries in Africa face a long hard road to recovery. The UK could catalyse and lead global support, change the future for developing countries, and strengthen UK soft power in the national interest.

Beyond the health and humanitarian impact, the combination of pandemic, lockdowns, and the international recession will initially hit consumption in low-income countries in Africa by as much as one third. This estimate, from our detailed modelling, has already been reflected in the drop in earnings in Kenya (here).[1] There will also be a hit to public finances, meaning tax rises and spending cuts of up to 10% of GDP. Restoring fiscal balance is key for economic recovery.

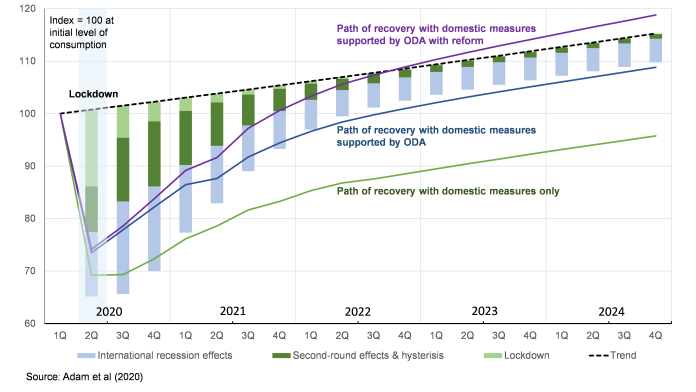

Figure 1: Simulated consumption spending after lockdown and global recession

Recovery would be strengthened by domestic reforms: to strengthen systems for tax collection and public spending. But all domestic policy choices facing low-income governments are grim: they cannot do ‘whatever it takes’. As put by the UK Secretary of State for the Department for International Development: low-income countries in Africa face a long and hard road to recovery.

International support, principally ‘Official Development Assistance’ (ODA) which would be anti-cyclical and short-term, would also accelerate recovery. Exceptional finance widens ‘fiscal space’, so that immediate policy choices are less awful; it relieves the need to raise taxes and cut spending, such as on social protection, health, and maintaining infrastructure – and it makes space for reform. Our modelling shows that if international finance is combined with reform, consumption could return to trend within three years; it would also sustain faster growth, and quicker poverty reduction (Figure 1).

To deliver, catalyse, or leverage international financing at scale, and to support feasible effective reform, is in the UK foreign policy and national interest:

- The Covid-19 pandemic is not defeated until it is under control everywhere. Otherwise there is a significant risk of a new wave of infection and death. Weakened public health systems failing to contain the virus is not in anyone’s interest.[2]

- What happens in Africa shapes what happens in the rest of the world because of demographics.[3] Africa’s population has a median age of 19 and will double by 2050. Faster recovery opens up the growth possibilities of a demographic dividend. It avoids the risk of increased concentration of poverty in fragile states.

- If economies stagnate south of the Sahara the pressure on young people to migrate in pursuit of work increases. The UK and Europe are not ready for more immigration and have an interest in accelerating recovery to build hope for jobs.

- This is an exceptional opportunity to project renewed UK soft power across the developing world by taking leadership of global support.[4] The unprecedented hit to low-income countries and the fact that they cannot do ‘whatever it takes’, means that they will be friends indeed for being in deep need.

We estimate that the additional international support needed to stabilise the fiscal position and accelerate recovery in low-income countries in sub-Saharan Africa is US$40-50 billion. The IMF estimate in this Op-Ed that an additional $44 billion is needed.

It is small, in global terms. US$40-50 billion is less than 0.5% of the now US$10 trillion being spent to combat the pandemic in G20 countries.[5] It is an increase of 29% in annual ODA. Debt relief since the turn of the century gives a precedent for this scale-up. We estimate the return on this financing in terms of accelerated gains in growth and consumption to be as much as 25%: it offers exceptional development value for money.

For the UK, this is an opportunity to take global leadership because what is needed is too much for any one bilateral donor budget to support. The UK has a track record in catalysing and leading multilateral coordination – it doesn’t have to be left to a multilateral, such as the World Bank.[6]

There is a risk to UK global interests that this moment is seized upon by the European Union as their opportunity to establish a new role as the coordinator of bilateral donors – as has been suggested by Germany.

In addition, central to UK leadership is that UK ODA has been pre-eminent in sophistication and effectiveness in impact and delivery – especially in technical support for reform.[7]

It is in the UK national interest to catalyse international support. The next question is: how could it be delivered? These are some of the opportunities for leadership:

- A fresh issue of Special Drawing Rights (SDRs) by the IMF. This proposal has been widely discussed, but blocked by the US.[8] It creates reserve assets and so does not ask donors to be ‘budget support cashpoints’. New SDRs are issued in proportion to country quotas at the IMF; a swap facility, or an initiative to make it easy for countries to lend or grant SDRs to low-income countries, would help re-distribute new SDRs in line with need.

- The proposal for fresh SDRs is appealing, but still needs leadership and coordination to turn it into a workable plan. If a new US administration removes the US veto early next year, then the 2021 Spring Meetings of the IMF and the World Bank would be an opportunity to turn aspiration into action.

- Development bank lending: balance sheets and loan to equity options. If the UK were to lend to development banks to bolster their capital, or re-purpose the ODA contribution to the budget of the European Commission to do the same thing, then it can be leveraged into more lending for budget support. This would be a basis to challenge the rest of the G20 to match UK action. An option to convert such loans into equity could offers a means to reform the balance of international representation.

- China is one of the biggest creditors to Africa. Engagement to move China beyond relief on debt obligations towards sustaining concessional finance would be astute in recognising a change in international official finance flows to Africa.

- Climate change: The international community has made pledges for substantial international transfers to fight climate change. The postponement of the COP-26 climate change conference in Glasgow to November 2021 makes space to create a package of financial support to low-income countries on climate change, including support for public finance reforms, to accelerate investment in green growth. That the ‘United Nations special envoy for climate action and finance’ is Mark Carney, the former Governor of the Bank of England, who has been appointed by the UK Prime Minister as finance advisor for the UK presidency of the COP 26 conference, points towards another opportunity for UK leadership.

The UK has an opportunity to project soft power and establish a new global role: catalysing and leading global support for low-income countries in sub-Saharan Africa will accelerate recovery from the devastation to growth, trade, and poverty that is being unleashed by the pandemic, lockdowns, and the global recession.

[1] Our detailed modelling has a rigorous estimate of the depth of recession and pathways to recovery: Adam, Henstridge, and Lee (2020) “After the lockdown: Macroeconomic adjustment to the Covid-19 pandemic in Sub-Saharan Africa”, Oxford Review of Economic Policy, forthcoming. DOI: 10.1093/oxrep/graa023 .

[3] See for example this in The Economist: https://www.economist.com/special-report/2020/03/26/africa-is-changing-so-rapidly-it-is-becoming-hard-to-ignore

[4] For a view on the political leadership, see: https://www.chathamhouse.org/expert/comment/getting-most-uk-aid-needs-political-leadership#

[5] ~The IMF has tracked that total here; the latest update comes from the IMF Managing Director here.

[7] How ODA should be delivered to support effective reform will be the subject of a separate note.