The impact of climate change on hydropower in Africa

EEG’s programme director Simon Trace explores the connection between climate change and renewable energy in Africa

-

Date

September 2019

-

Area of expertiseClimate, Energy, and Nature

-

KeywordsEnergy, resources and growth , Climate change adaptation , Climate change mitigation , Extractive industries , Green growth and investment , Renewable energy , Adaptive management , Policy implementation , Policy options , Technical assistance

-

ProjectsEnergy and Economic Growth (EEG) research programme , Improving climate resilience of local communities in southern Africa

One of the action areas for this year’s UN Climate Action Summit is Energy transition, which includes accelerating the shift away from fossil fuels and towards renewable energy.

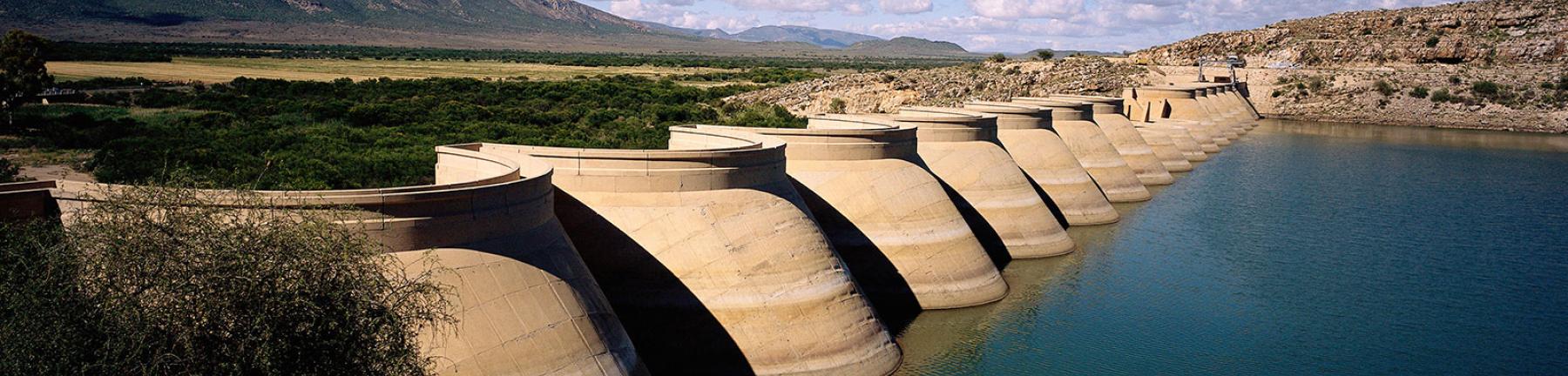

Hydropower has generally been viewed as a sustainable, clean, low-carbon source of energy* – but climate variability is putting its future under threat. Hydropower is particularly vulnerable to the effects of climate change – and the impact of the changes in rainfall and water availability, protracted drought events, significant variation in temperature regimes, and more frequent and severe weather events that are already being seen in sub-Saharan Africa.

Hydropower is flexible, reliable, and cost-efficient, and, being a clean, low-carbon source of energy, can significantly reduce global reliance on the fossil fuels responsible for climate change.

According to the World Energy Council, hydropower accounts for more than 70% of the world’s installed renewable power generation capacity. And, while it remains a largely untapped opportunity in the continent of Africa (it has developed only 7% of its potential, the lowest proportion of any of the world’s regions), it is a critical component of African governments’ plans to meet growing energy needs.

Hydropower in Africa

Some African countries have long seen the benefits, and are already highly dependent on hydropower for the majority of their energy supply. It accounts for over 90% of electricity generation in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), Ethiopia, Malawi, Mozambique, Namibia, and Zambia, and provides 20% of energy generation across the entire Southern Africa region.

Three of the largest rivers in the world – the Congo, Zambezi, and Nile – power most of this electrical generating capacity, with even more untapped potential in these rivers attracting much of the focus for future development. In total, roughly 80GW of future additional hydropower capacity is envisioned for Africa in the coming decades, with 28GW of potential hydropower located on the Nile and 13GW on the Zambezi. The Program for Infrastructure Development (PIDA), endorsed by African leaders in 2012, allocates nearly one-third (US$21 billion) of its priority budget allocation to hydropower.

However, as explained by a new EEG Energy Insight, opinions differ over whether the development of hydropower dams in developing countries should be prioritised. Many major schemes remain associated with serious social and environmental concerns, especially where large infrastructure and associated water storage has an impact on livelihoods that are dependent on the ecosystem services lost from the river. And even harder to predict and manage are the increasing constraints imposed by climate change.

The impact of climate change

Climate change has the potential to impact the hydropower sector through regional changes in rainfall and water availability, protracted drought events, significant variation in temperature regimes, and more frequent and severe weather events.

Potential impacts are estimated through scenarios projected across the expected lifespan of a hydropower dam, generally ranging from 50 to 100 years. The storage capacity and operational flexibility of most hydropower systems in Africa have been designed to account for historical patterns of hydrological variability, with contingency measures enabling the mitigation of dry periods. Most early-stage technical assessments, including the World Bank’s Hydropower Sustainability Assessment Protocol, continue to rely on historical hydro-meteorological records. But the long lifespan of hydropower infrastructure exposes their operations to decades of climatic variability, at a time when our capacity to accurately forecast climatic conditions is getting harder.

It’s likely that future conditions will be more variable than current or recent ones. This increased variability, and the potential longer-term implications of climate change, is not being adequately considered in the design of many hydropower schemes. Yet the effects of the exposure and vulnerability to climate change are already being felt.

Hydropower shortages in Zambia

In Zambia, for example, the large proportion of hydropower in the electricity mix leaves the country exposed to the variability of rainy seasons. Much of its hydropower capacity comes from four large stations owned by the electricity utility ZESCO: Kafue Gorge (990MW), Kariba North Bank (720MW), Kariba North Bank Extension (360MW), and Victoria Falls (108MW). Since 2013, generation has fluctuated, largely due to the impact of droughts on the water availability at large dams.

A recent EEG scoping study in Zambia revealed the severity of the country’s sensitivity to current rainfall variability. In 2014-2015, a drought led to a decline of 50 per cent of the country’s hydroelectric generation, starting a deficit that is becoming increasingly difficult to manage. The droughts resulted in extended load-shedding (greater than eight hours a day for many customers) aimed at preserving water and avoiding a complete shutdown of generating plants. To keep the economy running, especially the mining and agricultural sectors and SMEs, the Government of the Republic of Zambia (GRZ), through ZESCO, procured emergency power from heavy fuel oil (HFO) generators stationed on ships off the coast of Mozambique.

Beyond the direct costs of purchasing emergency power, GRZ analysis shows that GDP growth dropped from around 6% to a low of 2.6% following the droughts and subsequent blackouts. Although influenced by other factors as well, this indicates the significant impact drought can have on economic development.

In 2015 and 2016, Zambia was again severely affected by hydropower shortages, impacting productivity in its copper mining sector. In 2016 there was a deficit of around 600MW against demand, which necessitated expensive imports from the Southern African Power Pool (SAPP) region.

Although improved rain patterns and increased water flows contributed to increased generation in 2017, lower rainfall in 2018 and 2019 has again reduced reservoir levels and there is currently a deficit. ZESCO recognises that, at current generation levels, both the Kariba and Kafue dams will drain to their minimum operational limits by November 2019. Load management is being implemented with daily outages in place since May 2019.

Improving resilience

These recent events highlight how climate variability is threatening hydropower generation, potentially undermining infrastructure investments.

If warnings and climate projections are ignored, there is a serious risk of designing infrastructure that is not suitable for the climate of the future. To help make energy systems more resilient, we need to understand how climate change will continue to impact hydroelectric generation, and how to adapt hydropower production to extended drought conditions.

There is clearly an urgent need to effectively generate and integrate climatic projections into investment and decision making processes for the planning, design, and operational management of hydropower schemes. With a growing awareness and recognition of the risks, this process should be accelerated – and there is a need for partnerships between African governments, energy providers, and regional hydrological/meteorological agencies.

In pursuit of the Paris Agreement targets, countries must also look to integrate other renewable energy supplies, such as solar and wind, which will also reduce the climate exposure of high-capacity hydropower schemes.

We are working on a number of different initiatives that aim to improve the resilience of sub-Saharan African energy systems to climate change. The OPM-led Energy and Economic Growth (EEG) programme is implementing numerous research projects focused on the deployment of wind and solar in the region. We are also partner on the USAID-funded Resilient Waters programme, which is currently supporting the development of a series of high-level dialogues on critical issues facing the Southern Africa region – one of which is the climate-water-energy interface.

[button-link text="Discover our climate action content here" link="https://opml.co.uk/cop25"]

* Concerns have been raised about the impacts of carbon emissions associated with the actual construction of large dams and methane emissions from rotting vegetation in the reservoirs behind newly constructed dams under certain conditions, but hydropower is still generally viewed as contributing positively to low carbon energy futures.

Credit: This blog is based closely on material commissioned under the DFID-funded Energy and Economic Growth (EEG) programme: Katherine Cooke’s and Iliana Cardenes’ EEG Scoping Study in Zambia, and Chris Brook’s EEG Energy Insight, Will climate change undermine the potential for hydropower in Africa?