Bottom-up PDIA and the fishbone diagram in MUVA, Mozambique

“A tool for life, not just for business”

-

Date

October 2018

-

Area of expertiseCross-cutting themes

-

CountryMozambique

-

KeywordsGender, equality, and social inclusion , Office of the Chief Economist

-

ProjectMUVA: female economic empowerment in Mozambique

Blog post by MUVA's Rosie Pinnington and Iana Barenboim.

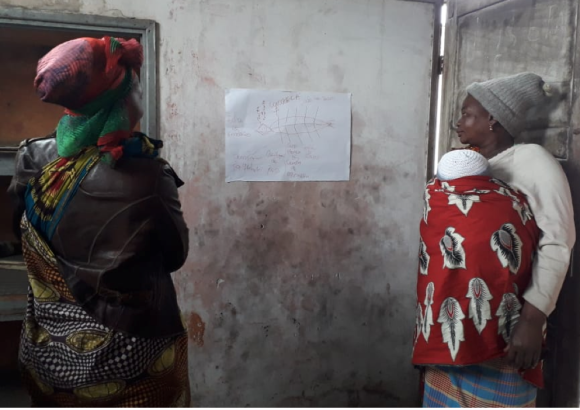

In OPM's DFID-funded MUVA programme, informal female market sellers have been using the PDIA-inspired fishbone diagram to diagnose their own problems. This has helped them identify the factors that limit their businesses’ growth, allowing MUVA to be led by the views and experiences of the women they seek to support. But, perhaps more importantly, it has facilitated the development of the problem-solving skills required for greater personal and professional growth amongst marginalised female market sellers. This, as one participant commented, makes the fishbone diagram “a tool for life, not just for business”.

There has been some question over how adaptive models can be used in the context of empowerment programmes like MUVA. What does the ‘doing development differently’ agenda mean when it refers to ‘locally led’ practice? Can an approach like PDIA really be applied outside of public sector reform? Does PDIA empower those on the receiving end of foreign aid and, if so, how?

Seeing women apply the fishbone diagram to their own lives, and benefit from the exercise, certainly points towards the value of PDIA beyond government-led reform processes. And, at least at the problem identification stage, it demonstrates how a PDIA-type approach can be used in a bottom-up development programme that seeks to empower vulnerable and disadvantaged groups.

In this case, marginalised female informal market sellers are not waiting for an expert to tell them what their problems are, and which technical solutions are required to overcome them. MUVA is developing problem-solving skills in the young women it seeks to support, so that they have greater personal control over their lives and can make more effective decisions related to their businesses.

Based on evidence that points towards limits in the effectiveness of traditional business training programmes, MUVA is focusing on a more promising approach. In addition to formal bookkeeping, financial management, and marketing, MUVA aims to promote proactive mindsets and entrepreneurial behaviours. These include acknowledging the participants’ capacity to overcome barriers (as they have struggled a lot to provide for their families), developing a ‘think outside the box’ and problem-solving mindset, and understanding their own personal barriers and potential as business owners.

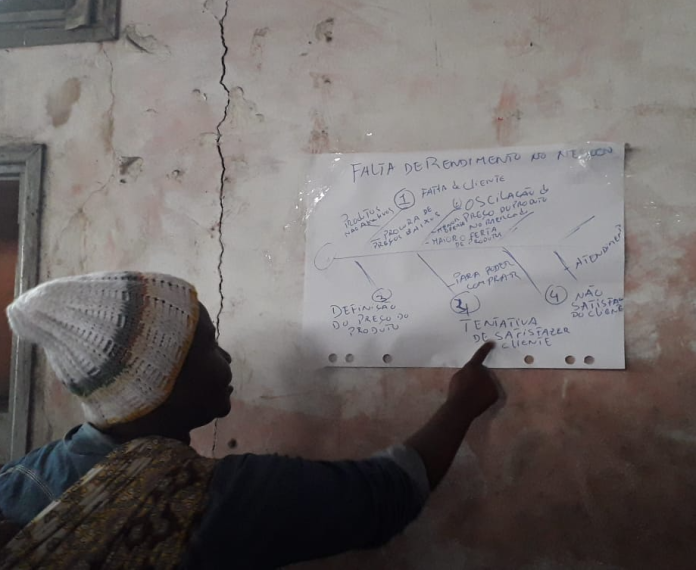

The fishbone diagram, which enables collaborative dissection of development problems by those who are actually experiencing them, is particularly well suited to this endeavour. MUVA asked the women to share problems in their businesses that are big enough for them to have difficulty in knowing where to begin or how to solve them. Nearly all of the women identified ‘business not making enough money’ as their primary problem. This is an obviously complex, or ‘wicked’, problem, where the causes are not immediately apparent, and a number of different causal factors are likely to interact or overlap. The structured dissection of causes and sub-causes enabled by the fishbone diagram is useful not just for MUVA, but for the women themselves.

If you go to an informal market in Maputo, you will very often see many traders selling the same product on a cloth, on the ground. To illustrate how this approach is being implemented, an example of a cause and sub-causes is the lack of clients, due to the lack of product diversification, due to the lack of confidence that the market sellers could sell different products from their mothers and grandmothers. Based on an understanding of this problem, MUVA uses participatory learning techniques to teach diversification strategies and creative behaviour. Training focuses not only on the technical side, but on the human side, especially the internal barriers these young women face in taking a step further.

This training model is closely linked to the MUVA programme’s wider approach to female economic empowerment, where the development of ‘soft skills’ like self-confidence, logical thinking, and body language are just as important as formal technical ones in unlocking barriers to economic opportunities. Across its projects, MUVA uses adaptive programming to shift the gender norms that prescribe what young women can and cannot achieve in Mozambique’s labour market. In this case, the fishbone diagram begins a process of adjusting how marginalised female informal market sellers view the potential of their own lives and businesses. Understanding their own problems is an empowering ‘first step’ in the development of ideas and strategies for seeing their businesses grow.

This article originally appeared on Harvard University's Building State Capability blog.