What factors affect the sustainability of education programmes?

Achieving sustainability – change that endures beyond current programmes – is a tantalising goal.

-

Date

May 2018

-

Area of expertiseEducation

-

CountriesIndia , Nigeria , Pakistan , Tanzania, United Republic of

-

KeywordSkills, livelihoods and education systems

It offers the potential of great value for money: catalyse change and see the benefits last for years without additional cost. Unsurprisingly, it is one of the five criteria recommended by the OECD's Development Assistance Committee for evaluating development assistance. But while there is a growing literature on the impact of education programmes, sustainability is rarely evaluated as rigorously, as most evaluations are undertaken before or just after programmes end, and as such little is known about what makes education programmes sustainable.

We looked across several education programmes we are evaluating and other reform programmes we are implementing to find answers.

Sustainability is hard to define

Sustainability signals benefits of an activity lasting after its end. For example, a one year in-service teacher training programme leads to changes in teacher behaviour in classrooms and better learning outcomes that outlast the programme. But this raises more questions, such as:

- For how long do improvements in performance have to be sustained? Is the training sustainable if teachers perform better until they retire, or just for the year?

- Do all the benefits have to be sustained? Is the training sustainable if teacher knowledge is better long-term, or should learning outcomes also remain better?

- Do the routines and behaviours around the activity also need to be sustained? Do teachers need to keep applying their new knowledge?

The difficulty of answering these questions means there are no agreed definitions of sustainability. Some people prefer to avoid the term altogether, in favour of irreversibility – i.e. making change difficult to undo. Programme funders, implementers, and evaluators need to discuss and agree in each case what sustainability might mean.

Sustainability has many elements

For performance to outlast activity, many factors need to be in place. There has to be performance in the first place – i.e. the activity has to cause some change of value. In addition, to overcome the pressure of competing alternatives:

- there must be strong stakeholder commitment particularly, but not only, from leaders;

- incentives and accountability systems must be conducive to keeping the work going;

- supportive processes and structures must be institutionalised in the relevant organisations;

- there need to be the right people with the right skills and attitudes to implement; and

- the programme must be affordable given the future fiscal context.

In an evaluation, the extent to which these conditions are met can be measured for separate components of a larger programme to form an overall judgement about a programme’s sustainability. This can be represented graphically, as in the figure below, where five workstreams (WS) are scored out of five against these elements.

Programme managers can also use these tools to work out where to focus their attention. Unless all these elements are in place at the relevant levels, it is unlikely that performance will be sustained. In our evaluations, education programmes are typically very vulnerable to changes in the views of leadership unless there is a deep and broad mandate supporting them, including unions, parent groups, and employers. Few programmes are able to change the incentive and accountability mechanisms, institutionalise structures and processes, or affect resource disbursements that are typically broader than the education system, even if they can build the skills of teachers in an affordable way.

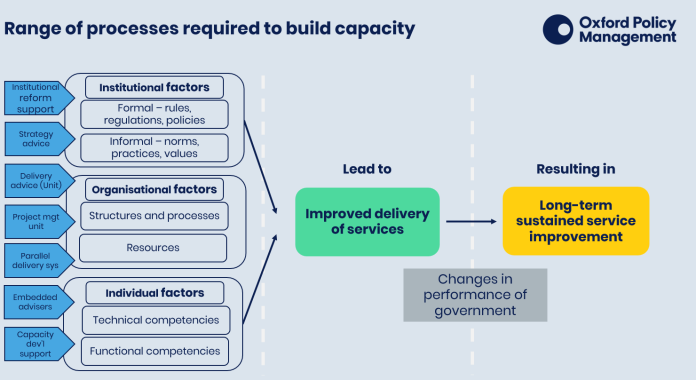

Sustainability and capacity are closely bound together

On this analysis, there are close connections between what makes programmes sustainable and what constitutes as capacity. Capacity to deliver (education) services requires the right institutional, organisational, and individual factors to be in place. The schematic below offers a reminder of the range of processes that are required to build capacity to deliver improved services long-term. Programmes typically focus on building individual technical capacity (e.g. training teachers) rather than the institutional and organisational factors that are much more difficult to affect and take longer to change. While stronger content and pedagogical skills in teachers are important, unless these other factors are in place, teaching and learning are unlikely to improve.

Note: this is a stylised diagram; the alignment is a simplification

These building blocks can be unpacked further and applied at different levels of the education system to inform efforts to build capacity and underpin attempts to evaluate success. For instance, individual competencies required for teachers, teacher leaders, head teachers, school supervisors, local government education officers, and ministry civil servants can be set out to inform training programmes. Few education systems have agreed competency matrices that are used to help staff at different levels set development goals and invest time in training and learning to help achieve their career objectives. Positions in education systems are too often allocated on the basis of qualification (e.g. a relevant degree) rather than competence (e.g. effective leadership and management). Structures, processes, and resources can be mapped against expected functions at various levels from schools upwards. Formal and informal institutional arrangements can be assessed across the education system using tools such as the Research on Improving Systems of Education (RISE) programme’s matrix on system coherence.

New education programmes that aspire to sustainability should at the least consider all these factors at the outset, and evaluations should bear them in mind.

Political economy is key

Since sustainability is likely to require changes in process, behaviour, and resource allocation that are difficult to achieve and likely to encounter resistance, it is important to have ‘reform space’ – the mix of authorisation to change, acceptance that change is required, and ability to make change. It is rare to have all three elements in place for as long as necessary, but programmes can improve the chances of having authorisation by mobilising a broad coalition of teachers, parents, employers, and politicians. Where space appears, take advantage to put in place some of the sustainability building blocks.

The will-o’-the-wisp of sustainability?

In folklore, a will-o’-the-wisp is a ghost that draws unsuspecting travellers from safe paths. Should we expect time-bound interventions in education systems to lead to long-term changes in performance? For some interventions, this is clearly an unrealistic goal. Training teachers for a few sessions in a year may improve teacher effectiveness for that year, but most teachers – and most people – need regular training, management, and support over a long period of time to sustain performance improvements. Changes in behaviours – key to almost any education process – take time to mature and normalise. More than this, as economies and societies change, the demands on education systems should evolve, and teachers will need to be trained to teach new material in new ways. So perhaps short-run teacher training is not an intervention that should be framed in terms of sustainability, lest policymakers be led down a path where they think further training will not be required.

As a parting thought, an alternative definition of sustainability sees programmes supporting an education system to become:

- self-improving using its own resources until processes are accepted as norms;

- adaptive in the face of new demands for different skills or attitudes; and

- resilient to shocks such as disasters, conflict, or economic collapse.

The difficulty of achieving all the conditions for sustainability is not a reason not to start working towards this vision of an education system, and making use of reform space where it appears. All programmes should be able to articulate how they can improve education system performance in the long run, and take care not to sacrifice this to short-term gains.

This blog is based on a series of internal seminars held by Oxford Policy Management’s education team reflecting on sustainability in education programmes in Tanzania, Nigeria, India, Pakistan, and elsewhere. While the views expressed remain those of the author, many thanks are due to the presenters (Rebecca Molyneux, Florian Friedrich, and Ben French) and all the participants in these seminars for helpful views and comments. Thanks in particular to Oladele Akogun for comments on a draft version.